With grief, sadness is obvious. With trauma, the symptoms can go largely unrecognized because they mimic other problems: frustration; acting out; or difficulty concentrating, following directions, or working in a group. Students are often misdiagnosed with anxiety, behavior disorders, or attention disorders rather than understood to have trauma that drives those symptoms and reactions. However, learning can also be a big struggle for children who have experienced trauma, and trauma-informed teaching can help.

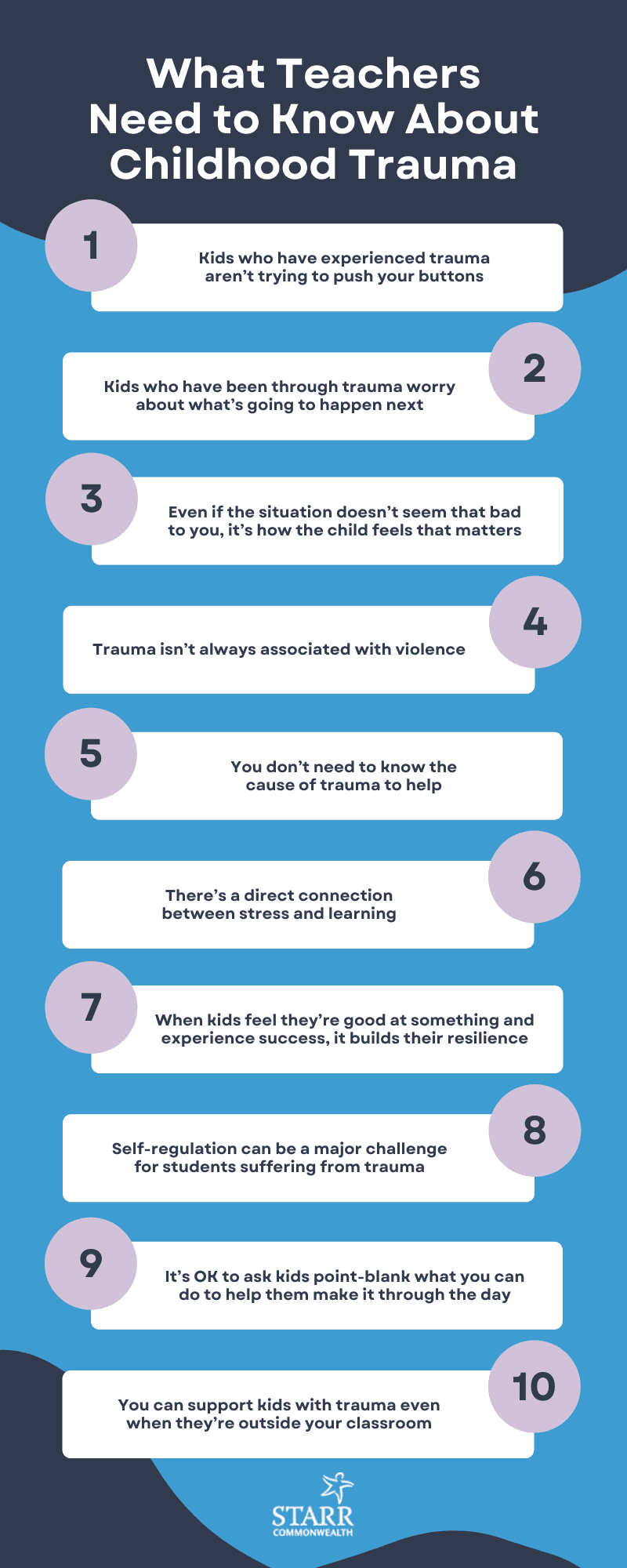

Here are 10 tips for understanding kids who have been through trauma, plus strategies to help them build resilience so they can bounce back and overcome their challenges.

1. Kids who have experienced trauma aren’t trying to push your buttons

If a child is having trouble with transitions or turning in a folder at the beginning of the day, remember that children may be distracted because of a situation at home that causes them to worry. Instead of reprimanding students when they’re late or forget homework, affirm and accommodate them by establishing a visual cue or verbal reminder.

“Switch your mindset and remember the kid who has experienced trauma is not trying to push your buttons,” says Caelan Soma, PsyD, chief clinical officer with Starr Commonwealth, an organization that offers resources to help schools build trauma-informed, resilience-focused communities.

These positive interactions might seem small, but they can build resilience in students, rewiring areas of their brains that have been impacted by trauma. On the other hand, starting the day with a reprimand can cause a child to shut down.

2. Kids who have been through trauma worry about what’s going to happen next

A daily routine in the classroom can be calming, so try to provide structure and predictability whenever possible. Since words may not sink in for children who go through trauma, they need other sensory cues, says Soma. Besides explaining how the day will unfold, have signs or a storyboard that shows which activity—math, reading, lunch, recess, etc.—the class will do and when. Knowing what to expect lets kids feel secure enough to focus on learning. With time, that can show kids that they have the resilience and power to do well in school.

3. Even if the situation doesn’t seem that bad to you, it’s how the child feels that matters

Trauma is highly individual. A situation that one person can easily recover from can cause trauma for another person. As caring teachers, we may unintentionally project that a situation isn’t really that bad, but how the child feels about the stress is what matters most, says Soma.

For some children, it may not be a singular event but rather the culmination of chronic stress. For example, a child who lives in poverty may worry about the family paying rent on time, keeping their jobs, or having enough food.

“Anything that keeps our nervous system activated for longer than four to six weeks is defined as post-traumatic stress,” says Soma.

The good news is that the opposite is true, too: small positive interactions, like greeting a student in the hall, might seem insignificant to you but can foster resiliency in your students.

4. Trauma isn’t always associated with violence

Trauma is often associated with violence. Yet, kids experience trauma from a variety of situations—like divorce, a move, or being over-scheduled or bullied.

“All kids, especially in this day and age, experience extreme stress from time to time,” says Soma. “It is more common than we think.”

You never know which student—or how many—can benefit from trauma-informed teaching.

5. You don’t need to know the cause of trauma to help

Instead of focusing on the specifics of a traumatic situation, concentrate on the support you can give children who are suffering.

“Stick with what you are seeing now—the hurt, the anger, the worry,” Soma says, rather than getting every detail of the child’s story.

Privacy is a big issue in working with students suffering from trauma, and schools often have a confidentiality protocol that teachers must follow. You don’t have to dig deep into the trauma to be able to effectively respond with empathy and flexibility. Instead, focus on trauma-informed teaching to create a classroom community that builds connections with students and lets them know you’re there to help them succeed.

6. There’s a direct connection between stress and learning

When kids are stressed, it’s tough for them to learn. Create a safe, accepting environment in your classroom by letting children know you understand their situation and support them.

“Kids who have experienced trauma have difficulty learning unless they feel safe and supported,” says Soma. “The more the teacher can do to make the child less anxious and have the child focus on the task at hand, the better the performance you are going to see out of that child. There is a direct connection between lowering stress and academic outcomes.”

7. When kids feel they’re good at something and experience success, it builds their resilience

Find opportunities that allow kids to set and achieve goals, and they’ll feel a sense of mastery and control, suggests Soma. Help build resilience by assigning classroom jobs students can do well or letting them help peers.

“It is very empowering,” says Soma. “Set them up to succeed, and keep that bar in the zone where you know they are able to accomplish it and move forward.”

Rather than saying a student is good at math, find experiences to let them feel it. Because trauma is such a sensory experience, kids need more than encouragement—they need to feel worth through concrete tasks.

8. Self-regulation can be a major challenge for students suffering from trauma

Some kids with trauma grow up with emotionally unavailable parents. The result is the inability to self-soothe. They may develop distracting behaviors and have trouble staying focused for long periods. To help them cope, you can schedule regular brain breaks and promote social-emotional learning. Tell the class at the beginning of the day when there will be breaks for free time, to play a game, or to stretch.

“If you build it in before the behavior gets out of whack, you set the child up for success,” says Soma.

A child may be able to make it through a 20-minute block of work if they know there will be a break to recharge before the next task.

9. It’s OK to ask kids point-blank what you can do to help them make it through the day

For all students with trauma, you can ask them directly what you can do to help. They may ask to listen to music with headphones or put their head on their desk for a few minutes. If a child isn’t able to name what will help them, try offering options: having a snack, going for a walk, or taking deep breaths, for example.

“We have to step back and ask them, ‘How can I help? Is there something I can do to make you feel even a little bit better?'” Soma says.

10. You can support kids with trauma even when they’re outside your classroom

Loop in the larger school, creating an ecosystem of trauma-informed teaching. Share trauma-informed strategies with all staff—from bus drivers to parent volunteers to crossing guards. Tell them how small interactions, like complimenting a student or offering a smile, can help kids with trauma build resilience.

Remind everyone: “The child is not his or her behavior,” says Soma. “Typically, there is something underneath that’s driving that to happen, so be sensitive. Ask yourself, ‘I wonder what’s going on with that kid?’ rather than saying, ‘What’s wrong with the kid?’ That’s a huge shift in the way we view kids.”

Looking for more ways to build resilience in your students?

Improve academic performance, reduce behavioral issues, and ensure all students in your classroom can flourish by becoming a Certified Trauma and Resilience Specialist in Education. This training provides detailed information and concrete actions that answer not just the “why” but also the “how” to create the best classroom and school supports for students and the school professionals who serve them.