I’m a SPED teacher with a decade of working with kids on the spectrum under my belt. In addition to teaching students with autism, I am happily married to an autistic spouse, and we have a child with sensory processing challenges. The most common question I get from colleagues who teach in mainstream classrooms is how best to reach their autistic students.

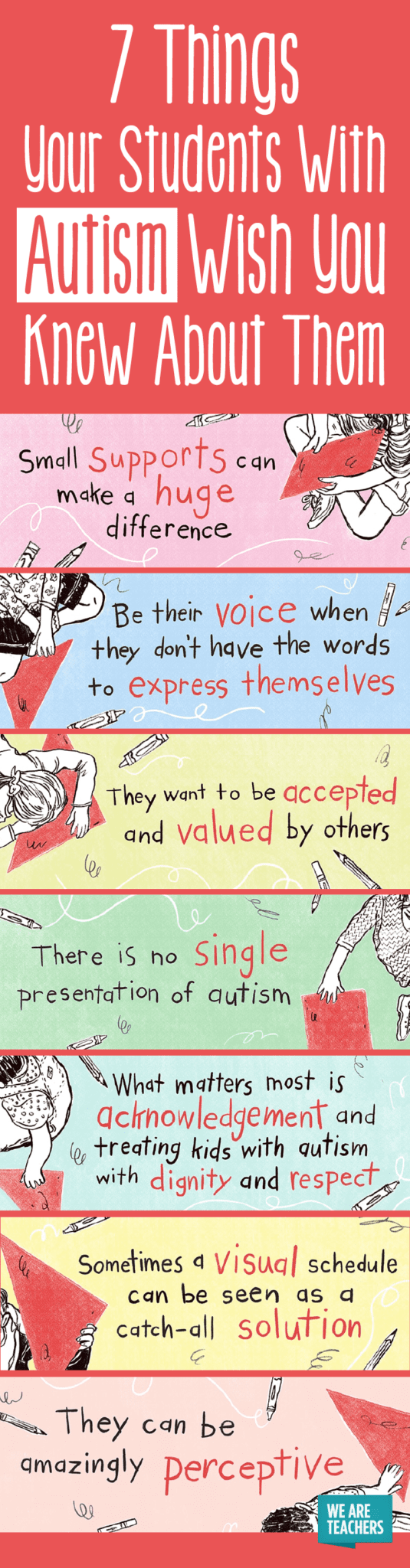

Autism is a fairly common diagnosis, with an estimated one percent of the population diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The CDC estimates that 1 in 68 children born will be diagnosed with autism. It is likely that most teachers will have one or more autistic students on their caseload. But it’s not always easy to know how best to reach these students. Here’s my list of seven things your autistic student wishes you knew about them:

1. They are all unique.

Seems kind of obvious, but it bears saying. Autistic people are as different from one another as folks without autism are, and there is no single presentation of autism. Not everyone with autism acts like Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man. Be open to learning the unique personalities and character traits of all of your students, autistic or not. You might be surprised by what you learn about them. Even better: You may even learn some new things about yourself!

2. Visuals help them understand, but they aren’t the only strategy.

One thing most autistic folks have in common is that they face challenges processing language. Even if the student can read fluently, it will likely be helpful to include visuals in their schedule or in their list of classroom expectations. This is my preferred visuals-creation website, and a membership is only $36 per year!

Sometimes, a visual schedule can be seen as a catch-all solution for students on the spectrum. Give it a shot and see if it helps. If it does, keep it. If it doesn’t, move on. There are lots of other strategies that you can use.

3. Just because they’re not looking at you doesn’t mean they’re not listening.

Generally, folks with autism are excellent listeners. They can be amazingly perceptive—almost to a fault. Yet, looking at them in class, they may seem off-topic or distracted. When you are speaking with them one-on-one, you may find yourself feeling frustrated with the lack of eye contact. Please try to resist the urge to ask them to look at you. Instead, gauge their engagement by their verbal responses or the improvement in their work.

4. A little support goes a long way.

Got a student on the spectrum who can’t sit still? Try a standing desk or a seat cushion. Always fidgeting with their hands? Each week, discretely place a new fidget on their desk and let them experiment. (In my experience, I have not found that fidget spinners help kids focus during work, although they can be great for sensory time. For work time, I would suggest small items with no moving parts, so that they don’t distract other students.) A visual timer can help them conceptualize time.

Make friends with your district’s OT. They will be your best ally in supporting your autistic students. Small supports can make a huge difference! And there’s more good news: Most sensory supports can be hacked for cheap.

5. They want to have friends.

We’ve come a long way from the idea that autistic folks are obsessed with themselves, as the first diagnosticians thought. Autistic children are just like any other children: They want to be accepted and valued by others. Sure, friendly relationships may look different for folks with autism (generally, their social stamina may be lower, and they may prefer to do “parallel play”—playing near others rather than with others). Some autistic folks may seek out computer- or technology-based social opportunities (such as social media) rather than face-to-face interaction, but they still have similar social needs as neurotypical people. Part of honoring our autistic students is honoring their social needs.

6. Ask them how they want to be described.

Sometimes we are a little uncomfortable about how to discuss folks with autism (and people with disabilities in general). Currently, there are two schools of thought: Person-first language is to say “person with autism,” and identity-first language would be to say “autistic person.” The preferred usage is being rigorously debated by the autism community, so it never hurts to do a bit of research for yourself.

Ultimately, what matters most is acknowledgement and treating folks with autism with dignity and respect. Autism is not a dirty word, and an autism diagnosis doesn’t make a person less worthy. Don’t let your discomfort with the language prevent you from talking to your autistic students directly or about them with your colleagues and other students.

7. They need you to provide a safe space for them.

People with autism and sensory processing disorders may experience everyday events as terrifying but are unable to express this. School can be a scary place for autistic students. They need you to be in their corner and to provide them with support. Positive acknowledgement of their achievements is important. Be their voice when they don’t have the words to express themselves. They need you to see beyond their differences and recognize their potential.

Your investment in the lives of your students with autism will pay huge dividends. Many of my most meaningful moments and relationships have been with folks on the spectrum. If you are so lucky as to have a student (or a few) on the spectrum, you will soon learn that they are a wonderful addition to your classroom.

Is there anything you would add to this list? What has been your experience teaching students with autism? Come share in our WeAreTeachers Chat group on Facebook.

Illustrations by Brenna Thummler for WeAreTeachers